A History of Blacksmithing in Germany

If you could walk through a German village in the Middle Ages, one of the first sounds you would notice would likely be the steady, ringing rhythm of a hammer striking an anvil. The blacksmith’s forge was impossible to miss: sparks flying, smoke rolling from the chimney and the glow of the fire spilling out into the street. For centuries, this was the soundtrack of life in many German towns, a reminder that almost everything people needed—tools, horseshoes, weapons, nails and hinges all passed through the hands of a smith.

The story of the blacksmith stretches back much further than medieval times. More than two thousand years ago, long before the Roman Empire or even the arrival of the Romans, people in the Siegerland region of modern North Rhine–Westphalia were already smelting iron. They built small bloomery furnaces that produced lumpy sponges of raw iron. These weren’t the huge, roaring blast furnaces that are used today to produce massive amounts of perfect steel. They were humble clay towers, smoky and temperamental, and the iron they produced was full of impurities. Early smiths had to hammer the bloom again and again, folding and forge-welding it until it became usable. It was exhausting, hot and dirty work, but it gave them something precious: a metal far tougher and harder than bronze.

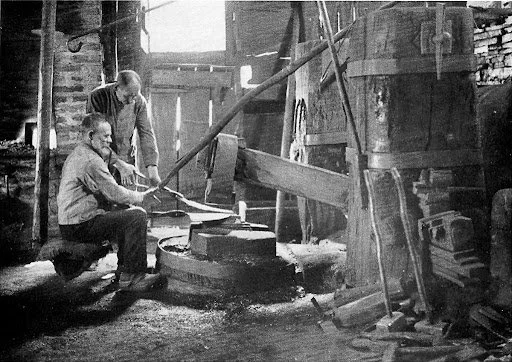

An example of an old bloomery furnace made from clay

Further east from North Rhine–Westphalia, in the Lahn-Dill region of Hesse, another transformation was happening. Streams provided water to turn trip hammers and bellows, local forests were stripped for wood to make charcoal, and the hills gave up their coal and iron ore. These places became landscapes of fire and iron, where smithing wasn’t just a trade but part of daily survival. When archaeologists dig there today, they still find the slag heaps and furnace remains that testify to how much iron was worked, even before written history caught up.

A blacksmith working at a trip hammer powered by a nearby stream

By the Middle Ages, blacksmiths had become indispensable. Every village needed one. Everyone from a farmer with a broken ploughshare in spring, to a traveler whose horse had lost a shoe on a muddy road needed the blacksmith's expertise to solve their problems. In rural areas, the village smith was a jack-of-all-trades and often had his workshop in the middle of the town. He’d fix a wagon wheel one day, forge door hinges the next, and shoe horses whenever needed. In the bigger towns though, things were more formal. Smiths belonged to guilds which were powerful associations that regulated who could practice, how apprentices were trained, and what standards had to be met. These guilds were about more than economics, they gave smiths an identity, protection, and pride.

Becoming a smith wasn’t easy in the middle ages. Boys apprenticed typically for four to five years, fetching water, turning bellows, and slowly earning the right to work at the fire themselves. Once they had mastered the basics, they set out on their journeyman’s travels. They would leave their home and their master's workshop with a bundle on their back and a hammer at their side. They then wandered from town to town, working in different smithies, learning new techniques, and seeing the world one forge at a time. These journeys often lasted years, and when he returned, the aspiring smith had to prove himself by creating a masterpiece that showed his skill and knowledge of the craft. If his piece passed inspection, he could finally open his own shop. From apprentice to master craftsman typically took ten to twelve years in the middle ages. This is known today because of the detailed records held by the guilds during that time.

As centuries rolled on, some towns became famous for their smiths. Passau, on the Danube in Bavaria, was one of the earliest to gain fame. By the 14th century, its swords carried a little wolf mark, called the the `Passauer Wolf´ that was often inlaid with brass. To soldiers, that mark meant the blade was reliable, and perhaps even lucky. Legends sprang up that Passau swords had magical powers that would protect their owners in battle. Even though that was probably not the case, the mark of the Passauer Wolf gave blades a reputation amongst soldiers across Europe.

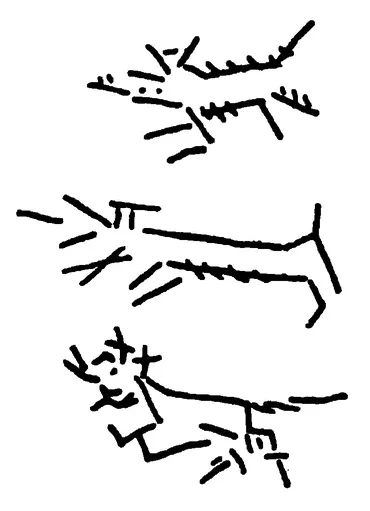

Passauer Wolf marks as would have been chissled into Swords

As Passau was known for its swords, Solingen, near Cologne, would become known for its production of various high quality sharp utensils. The first records of Solingen blades appear in the 13th century. By the 1400s, its grinders and hardeners had guild rights, and from then on the city grew into what Germans still call the “City of Blades”. Solingen had many advantages: fast-flowing rivers to power smithies, forests for charcoal, nearby iron ore from Siegerland, and the trade routes of Cologne for getting goods to market. Solingen’s knives, razors, and scissors became famous around the world and still to this day, “Made in Solingen” is a mark of quality that is protected by German law.

Scissor dies from Solingen

In the forests of Thuringia, in the town called Suhl, another kind of smithing took root. Gunsmithing flourished here from the 1300s onward, gaining fame by the 1500s for finely crafted muskets and rifles that found their way into courts and armies all across Europe. Despite devastation from the Thirty Years’ War in the 1600s, the gunsmithing craft rebounded, and by the 18th and 19th centuries Suhl had become a hub of innovation, with renowned firms like Sauer & Sohn, Haenel and Merkel producing everything from luxury hunting rifles to military carbines. Future wars fueled demand, but after 1945 Suhl fell under Soviet control, its companies nationalized into a vast state enterprise that produced everything from firearms to motorcycles, while still preserving centuries-old craftsmanship and hosting Germany’s only armorer’s school. Following reunification in 1990, the old conglomerates collapsed but Suhl’s legacy endured. Sauer, Merkel, and Haenel still continue to thrive, blending modern technology with traditional engraving and hand-finishing, all rooted in the hammer-and-anvil traditions of the town’s smiths.

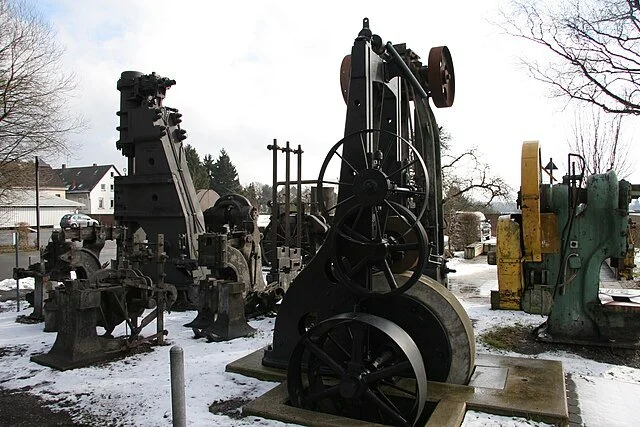

Technology has reshaped the way blacksmiths work. Medieval smiths discovered the power of water. Streams that had once turned millstones now drove massive wooden hammers, pounding out iron bars at a rate that would be impossible to match by hand. By the 19th century, factories were full of mechanised drop hammers powered initially by flowing water from the nearby rivers then later by steam and later still with electric motors. Solingen’s Hendrichs drop forge, founded in 1886, was one of these mechanised factories. Inside, the air shook with the crash of steel on steel, stamping out knife and scissor blanks by the thousands. The blacksmiths still finished the blades by hand, but the rhythm of the forging industry had changed forever.

Modern machines from the Hendrichs drop forge in Solingen

Not every forge in Germany was devoted to mass production or weapons. Alongside the clang of drop hammers and the bustle of blade factories, there were countless smaller workshops where iron was coaxed into beauty as much as utility. From as early as before the Gothic period, smiths were twisting metal into inrticate vine-shaped hinges, tracery-filled window grilles, and fences that looked as if they’d grown straight out of the earth. By the Renaissance and Baroque eras, decorative ironwork grew into ever more elaborate—balconies, gates, staircases and railings, flowing with curling leaves, flowers, and scrolls, like plants and other natural elements frozen in time. These pieces weren’t just practical hardware; they were works of art, built into churches, townhouses, and gardens across Germany.

A window grille forged by Karl Paul Marcus

An advertisement for Karl Paul Marcus 1889

That artistic streak carried forward into the modern era. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, masters like Karl Paul Marcus in Berlin and Carl Wyland in Cologne pushed the boundaries of decorative ironwork, creating everything from gates and lanterns to fountains and architectural pieces that traveled far beyond Germany’s borders. Even after World War II, when East German workshops were nationalized and repurposed, smiths managed to keep artistry alive in restoration projects and culturally significant commissions.

A gate by Carl Wyland in St. Georg, Berlin 1925

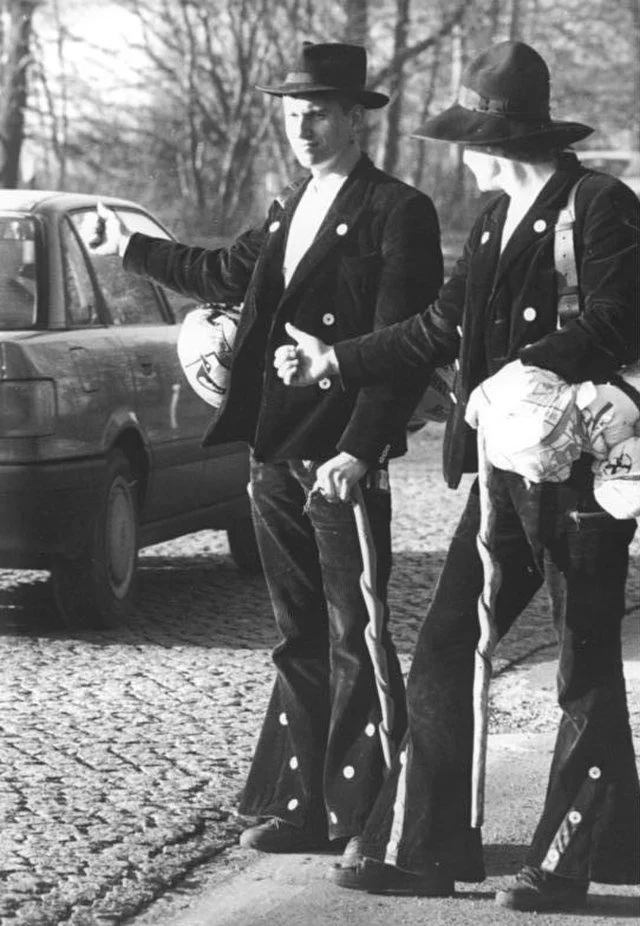

Today, blacksmithing is no longer at the center of daily life, but it hasn’t disappeared completely. In Solingen, the Deutsches Klingenmuseum tells the story of blades from the Stone Age to the present, while the preserved Hendrichs drop forge lets visitors feel the thunder of 19th-century mechanized forging. In Suhl, the Waffenmuseum showcases six centuries of firearm production. Across Germany, a number of highly skilled artisan blacksmiths still practice the old craft of forging by hand and with some use of modern machines to create fine artistic ironwork in gates, railings, and sculptures that uphold the spirit of traditional blacksmithing. The tradition of the journeyman’s travels is still alive and practiced by a few although it’s no longer a necessity for becoming a qualified blacksmith. Every so often you’ll see a craftsman in traditional garb, hammer on his belt and a bag over his shoulder, travelling from town to town just as they did hundreds of years ago. It is still required by law that a blacksmith has to have a master craftsman qualification in order to open a smithy in Germany.

Traditionally clothed journeymen

Blacksmithing in Germany may have changed its face over the centuries, but its heart is still beating steadily. From the smoky bloomery furnaces of the Iron Age to the roaring drop hammers of Solingen, from village smiths mending ploughshares to artists shaping iron into curling vines and scrolls, the craft has never stopped evolving. What began as a matter of survival grew into a mark of skill, pride, and artistry that still leaves its trace on gates, rifles, and railings across the country. Today, whether in museums that echo with the clang of preserved forges or in the hands of modern smiths carrying on the old traditions, the story of German blacksmithing reminds us of the timeless human desire to take raw earth, fire, and iron—and transform them into something enduring and beautiful.