The Acanthus Leaf: Twenty-Four Centuries of Craft and Symbolism

There's an old story that the Roman architect Vitruvius tells about how the acanthus leaf became one of the most enduring motifs in decorative arts. A young girl died in Corinth, and her nurse gathered some of her belongings in a basket, placing it on the grave and covering it with a roof tile for protection. An acanthus plant grew up and around the basket, its leaves forced outward by the tile, causing them to curl up. The sculptor Callimachus, passing by, noticed this arrangement and was inspired by the form to create what would become known as the Corinthian capital.

A drawing of a Corinthian capital

Whether this tale from the first century BC is fact or legend doesn't really matter. What's compelling is how it captures something essential about the acanthus: it's a plant that adapts, persists, and finds beauty even in difficult circumstances. That symbolism has carried the motif through more than two millennia of decorative arts, from ancient Greek temples to a variety of decorative crafts being done today.

The real acanthus plants that inspired this tradition are the native Mediterranean plants called the Acanthus spinosus and Acanthus mollis. They have deeply lobed, sometimes spiny leaves that can grow quite large. These characteristics made them perfect subjects for architectural and other decorative ornamentation. The complex shapes of the leaves offered endless possibilities for artistic interpretation that would be expressed in a large variety of materials and media; from chiselled stone to forged steel and wooden carvings, the Acanthus leaf can be found all over Europe.

A cornice stone from circa 705-715 AD

The Greeks were the first to incorporate acanthus leaves into architectural ornament around the fifth century BC, using them primarily in Corinthian capitals. The oldest known example of a Corinthian column is in the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae in Arcadia, around 450-420 BC, though the order was used sparingly in Greece before the Roman period. Their interpretation stayed relatively close to the natural form, with careful attention to the plant's characteristic lobes and veining. Greek sculptors understood that the acanthus's beauty lay not just in its complexity but in its organic forms that could be frozen in stone yet somehow still alive with movement.

The Romans embraced the acanthus with characteristic enthusiasm, developing it far beyond its Greek origins. They elaborated the order by curling up the ends of the leaves in a dramatic, organic way. It soon became one of their favourite ways to decorate their buildings. Roman craftsmen began to see the leaf not as a botanical study but as raw material for artistic invention. They stretched the forms, combined them into elaborate scrollwork, and wound them around columns in spiraling friezes. The leaves became artistic forms found on sarcophagi as symbols of eternal life and covering architectural surfaces with luxurious decoration. Roman sarcophagi, characteristic of elite burial practices from the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD, were often carved with garlands of fruit and acanthus leaves. Roman blacksmiths also incorporated the motif into bronze fittings and domestic objects, democratizing what had begun as temple ornament.

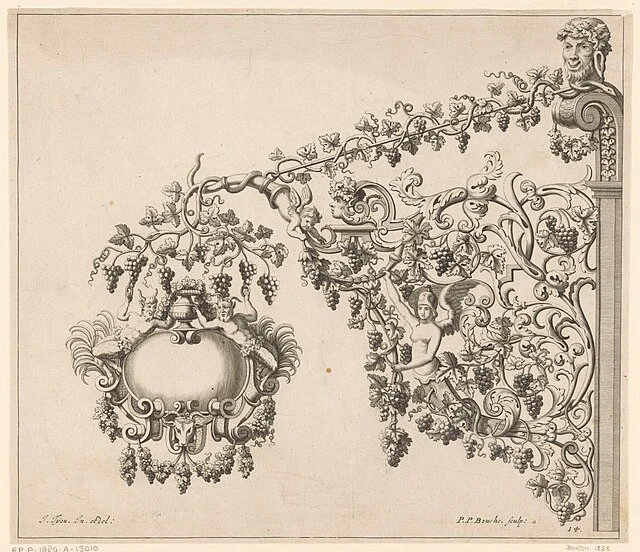

Acanthus design by Alexis Peyrotte

When Rome fell, the acanthus didn't disappear but rather evolved to meet new cultural needs. Byzantine craftsmen developed sophisticated techniques for chisling acanthus decoration into stone, creating leaves that seemed to float free from their backgrounds through deep undercutting and careful attention to light and shadow effects. The Byzantine interpretation showed remarkable technical skill, with craftsmen learning to create dramatic contrasts that made the stone ornament appear almost weightless.

Medieval craftsmen approached the acanthus differently depending on their medium and cultural context. Stone masons working on Romanesque churches simplified the forms into more geometric patterns that complemented the architectural style's emphasis on mass and weight. Manuscript illuminators drew acanthus borders in flowing, stylized spirals that could grow across parchment pages, often combining the leaf with Christian symbols. The design of the acanthus leaf carvings became less naturalistic and more stylized, yet the design element persisted through various cultural transformations.

The Renaissance brought renewed interest in classical antiquity and with it a careful study of Roman acanthus forms but Renaissance craftsmen weren't simply copying ancient models. They were reinterpreting them through the lens of humanistic scholarship and direct observation of nature. Woodcarvers working on furniture and architectural details developed techniques that allowed them to create leaves with remarkable depth and naturalism. Stone masons revived the Byzantine practice of deep undercutting, creating architectural ornament that seemed to breathe with life and movement.

A heavily undercut stone capital in Zürich

Each material demanded its own approach to the acanthus, revealing distinctive techniques and results. Stone masons, working with the natural fracture lines and density of their medium, could achieve fine detail and deep undercutting, using the stone’s ability to hold crisp edges to create intricate patterns of light and shadow that shift throughout the day. In contrast, wood carvers developed strategies that responded to grain and growth rings, orienting leaf forms to take advantage of the wood’s natural strength and producing delicate, flowing edges impossible to achieve in stone. The difference between materials is especially clear in the handling of the acanthus’s characteristic curves and spirals: wood carvers, using sharp gouges and chisels, follow the grain to create leaves that seem to grow organically, as if revealed rather than imposed, while stone masons must work deliberately against the harder material, planning each chisel cut to build the leaf form through a careful balance of removal and preservation.

For blacksmiths, the Renaissance brought a new chapter in the evolution of the acanthus motif, as iron offered possibilities that neither stone nor wood could match. Hot metal could be shaped into plastic, flowing curves and twisted spirals that captured the leaf’s organic energy with remarkable vitality. Early forged acanthus designs of the late Gothic period were relatively flat and geometric, but by the Baroque era, smiths had developed sophisticated techniques that produced leaves appearing to grow and curl with lifelike movement. Unlike carving, forging does not involve removing material but rather adding form through controlled deformation; each hammer blow shapes the leaf, builds texture, and gives it character. Under heat, iron becomes malleable, allowing the creation of intricate, delicate edges that seem to flutter while retaining the inherent strength of steel, forms nearly impossible to achieve in other materials.

A design by French blacksmith Jean Tijou

Jean Tijou, the French master blacksmith working at Hampton Court Palace from 1689 to 1700, demonstrated the full potential of forged acanthus. His baroque screens featured elaborate scrollwork where acanthus leaves seemed to grow organically from the metal itself, incorporating swirling forms, swags of flowers, and heraldic symbols. Tijou's work showed how iron could capture not just the acanthus's form but its essential vitality.

Right and below, Hampton court screens by Jean Tijou

The techniques for forging an acanthus leaf haven't changed over the centuries. The basic technique is as follows: You start with heated iron or steel, drawing out the metal to create the leaf's basic shape in a flattened form. Then you use various chisels to cut out the refined form of the flattened leaf which defines its outer edges. After that, you use rounded punches and blunted chisels to define the central vein and other major divisions on the leaf. Next, you use various punches, dies and driving hammers on a wooden stump that has a collection of hollows and roundings on it to forge the three dimensional curves into the once flat metal surface. The final step involves heating specific areas and using scrolling tongs to create the characteristic curls and spirals that give the leaf its sense of natural movement.

The eighteenth century brought different interpretations across all media. During the Rococo period, acanthus leaves became lighter and more playful in every material. Stone masons created asymmetrical compositions with leaves that seemed to dance across architectural surfaces. Wood carvers developed techniques for creating leaves so delicate they appeared ready to be blown away by the next breeze. Blacksmiths forged leaves with impossible curves and spirals that defied the apparent limitations of their material.

Neoclassicism brought a return to stricter classical models, but with a new understanding of historical development. Craftsmen in all media studied Roman and Greek examples more systematically, creating works that were simultaneously archaeological and contemporary. The Victorian era democratized the acanthus through industrial production in cast iron, while hand-crafted versions in all materials retained their special character.

A cast iron window grille from 1937

Today, craftsmen continue to work with the acanthus across all traditional media, some reproducing historical patterns with careful attention to period details, while others adapt the form to suit modern aesthetic sensibilities. Wood carvers explore the motif's possibilities in exotic hardwoods that earlier generations never saw and stone masons use diamond tools to achieve effects that would have been impossible with traditional steel chisels while blacksmiths continue to discover new ways that heated iron can be coaxed into organic forms using modern machines and tools.

The acanthus endures across materials and centuries because it embodies something fundamental about the relationship between nature and human creativity. In the Mediterranean world it came to stand for enduring life, rebirth and immortality, likely because of the plant's very hardy nature, re-growing year after year. Its interesting form is complex enough to challenge skilled craftsmen while being simple enough to be readable at architectural scale, and meaningful enough to carry symbolic weight throughout the ages. Whether chisled in marble, carved in wood, or forged in iron, the acanthus reminds us that the best decorative work doesn't just copy natural forms. It interprets them, finding in a humble plant a symbol rich enough to inspire artists across twenty-four centuries of continuous tradition.